|

||

| Recordings to celebrate the world of the oboe | ||

|

CD DETAILS (click what you want to see)

|

|

Other 'historical' CDs:

|

(Click underlined players to hear MP3 format sound clips.)

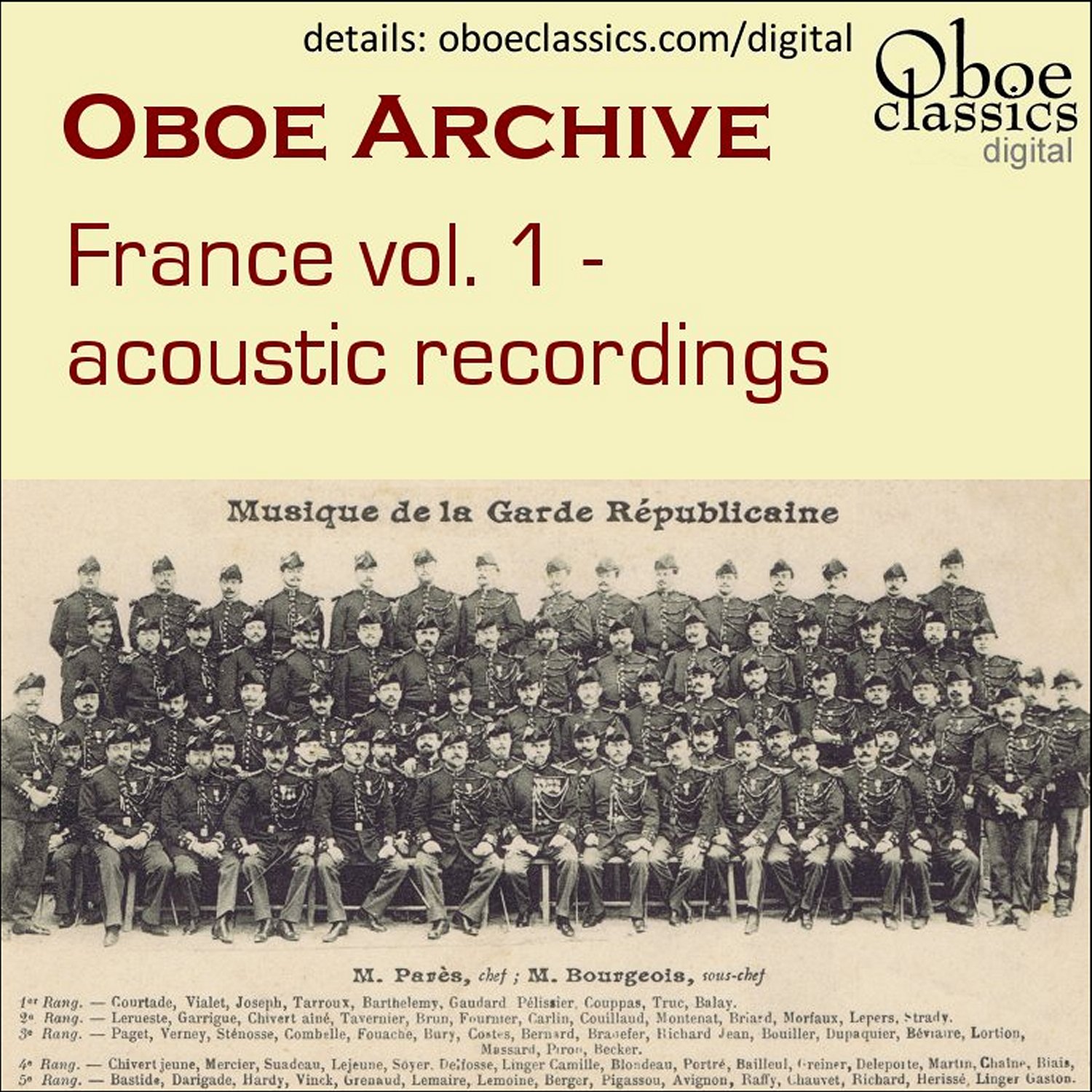

CD I (time: 70:55)

Caesar Addimando Carmen, Petite Mignon (1908); Georges Gillet (c1905), ‘Giorgio’ (1906) Rossini, Guillaume Tell; Housset Huguenin, La nuit de Noël (1903); Joseph Fonteyn Guilhaud, First Concertino and Farandole (c1910); Louis Gaudard (c1910), Louis Mercier (c1910), Paul-Gustave Brun (c1926) Leroux, Une Soirée près du lac; Arthur Foreman Schumann Romance no. 1 (1911); Georges Longy Colin, Concertino in D, Andante and Polonaise (1914); Léon Goossens Mozart, Oboe Quartet K370 (1926); Georges Blanchard (1927), Bruno Labate (1929), Anon oboist (1950) J C Bach Sinfonia in Bb; Fernand Gillet Satie, Gymnopèdie 1 (1930); Svend Christian Felumb Nielsen, Romance and Humoresque (1937)

CD II (time: 69:09)

Myrtile Morel Milhaud, Suite d’après Corrette (1938); Louis Bleuzet Mihalovici, Sonatine Op 13 pour hautbois et piano (1939); Louis Gromer Handel, Sonata in F (c1940); Henri de Busscher Tchaikovsky 4th Symphony, Rimsky-Korsakov Schéhérézade, Brahms Violin Concerto 2nd movt (excerpts, 1940s); Fritz Flemming (1927), Léon Goossens (1936), Marcel Tabuteau (1945) Brahms, Violin Concerto opening of 2nd movement; Lois Wann, Ferdinand Prior and Engelbert Brenner (1939), Sidney Sutcliffe, Roger Lord and Natalie James (1951), Hans Kamesch, Manfred Kautsky and Hans Hadamowsky (1953) Beethoven, Variations on 'La ci darem'

with a description of each performer, each track, and many unusual photographs.

Note: These are two CDs for the price of one.

Introduction by compiler Geoffrey Burgess:

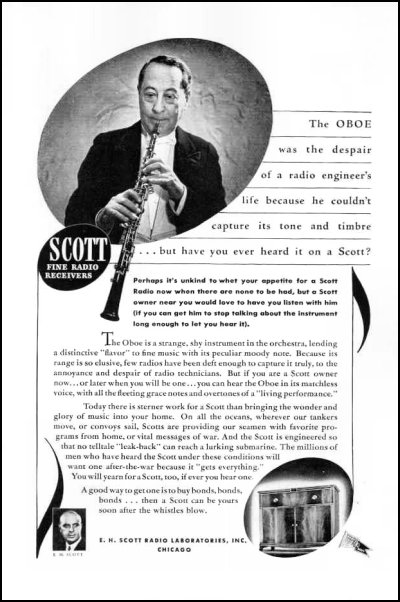

It would be hard to claim the oboe as a main player in the rise of the phonograph in the early years of the twentieth century. In both contemporary literature and retrospective histories, oboists barely rate a mention alongside the Carusos, Melbas, Elgars and Kreislers, and the lack of a comprehensive discography or historic anthology backs this up. But why have early oboe recordings been silent for so long? It is time to discredit the popular belief that of the few recordings of oboists that have survived, most are worthless from a musical standpoint.

While not featured as frequently as most other instruments, the oboe was not entirely silent in the recording studio: however, the problem lies much more in how and where to retrieve those distant echoes. Catalogues, reviews and the like cite specific recordings, but this is only a beginning. The next and harder step is to track down serviceable copies of this material which in most instances was considered of merely ephemeral value.

We have to consider ourselves lucky with what has survived. Contrary to what we might think, the scarcity of oboe recordings is not a reflection of the difficulties encountered in capturing its tone. Even the earliest acoustic recordings demonstrate that, with the player projecting directly into the recording horn, the oboe sounded better than many other instruments. The reason for the scant presence of the oboe on disc has to do more with its musical and cultural persona. Just as now, the recording industry in the early decades of the twentieth century was dictated by popular taste. Not only did the Classical selections in gramophone catalogues constitute a small percentage of the total offerings, but they were dominated by operatic excerpts and rousing tunes performed by bands. In such a climate the oboe was not exactly a winner, rather it was considered a novelty, of interest to the refined connoisseur.

It’s not needles, but the records themselves that need hunting down in the haystacks of archival repositaries and collectors’ attics. Artists’ names and instruments were given only rarely on the discs. Manufacturers’ catalogues can help but it is often necessary to resort to intelligent guesswork.

According to the renowned audiofile Melvin Harris, it was Louis Gaudard who made the earliest oboe recording in 1899, but this claim is still to be substantiated. The oldest surviving recordings date from the first decade of the 20th century, with showy solos of ephemeral appeal usually accompanied by band, orchestra or, more rarely, piano.

Despite the scant examples, we are blessed with multiple recordings of some favorites such as Une Soirée près du lac and standard orchestral repertoire like the overture to Guillaume Tell. These multiple versions allow direct comparison between different oboists, although it should always be borne in mind that the different settings and the recording process contributed in no small measure to the total sonic record.

This anthology spans the acoustic and electric eras and all recordings are monoaural. Léon Goossens was the most widely recorded oboist of the first half of the 20th century, but otherwise, all of the oboists featured in this anthology were active before the rise of the oboe “heroes” still familiar today - André Lardrot, Pierre Pierlot, Heinz Holliger, etc. Many were celebrated in their own day, but most are now forgotten. We have intentionally avoided duplicating the already copious quantity of re-released material. Oboists like Roger Lamorlette, who can be heard playing Poulenc’s trio for oboe, bassoon and piano with the composer, have been omitted, and well known players like Goossens and Tabuteau whose work is already widely available, are represented only by noteworthy selections hitherto unavailable.

There is no natural terminus ad quem for this anthology. Stylistic changes in oboe playing tended to overlap advances in recording technology in complex ways. Still, it seems appropriate to draw the line at the mid century with the dawn of the LP era with the Viennese recording of Beethoven’s variations on La ci darem (CD II track 21).

Direct contact with these remarkable performances from the past is still hampered by the limitations of the available recording technology and the state of preservation of this delicate material. Most of the original recordings used here are in an exceptionally fragile state and the audio quality of many is quite simply deplorable. Any wax cylinder or shellac disc that has miraculously survived the junk yard inevitably bears the signs of abuse - damaged through overuse, poor storage conditions, or the jostle of the flea market before falling into the hands of a responsible collector. Every effort has been made to locate clean copies, but in some cases there was simply no choice.

To understand these vestiges of players from the past, we have to learn to listen “through” the recording technology. Most early recordings have what today would be an unacceptable signal-to-noise ratio. The distraction of surface noise and crackles and limited frequency response and can hinder drawing conclusions on individual players’ tone. Most acoustic recordings registered a relatively narrow band of frequencies from 1000-3000Hz. With the introduction of microphones this was expanded to 200-6000Hz, but this is still far short of present standards which were set in the stereo LP era at 20Hz-20KHz. To those used to digital stereo, the monoaural configuration of early recordings may seem one-dimensional and, particularly in the case of acoustic recordings, the insensitivity of the technology to dynamics often obliterated nuance, and can also give a false sense of balance.

At the same time we must listen “with” the technology. That is, we must learn to respond to what the technology could register faithfully - tempo, intonation, vibrato and questions of ensemble - always mindful that, once in the recording studio, players may have had to make adjustments from their regular practices. Up to the use of magnetic tape in the recording process in the 1940s, all recordings were “live” in the sense that virtually no editing was possible. Realizing that durations of 2 to 4 minutes (the length of a side of a disc) were recorded as complete takes makes it easier to forgive occasional slips - indeed, it should enhance our admiration for these players.

It is always dangerous to draw general conclusions from limited data, so rather than viewing these recordings as documents of the essential characteristics of each oboist, it is wiser to treat them as “snapshots” of unique performances. Out-of-focus or underdeveloped due to the shortcomings of the recording apparatus, these passing glimpses are the closest we can get to the artistry of these lost musicians.

Despite this material’s limitations, it’s revelations are manifold. The recordings of Georges Gillet CD I track 2) and his pupils (Gaudard, CD 1 track7; Mercier, CD I track 8; Brun, CD I track 9; Longy, CD I track 11; and Bleuzet, CD II tracks 5-8) show that prior to World War II French players did not all cultivate the bright tone typical of the younger players of the Paris Conservatoire school. We can appreciate why Tabuteau praised Bruno Labate (CD I track 16), and why Goossens could not have failed to have been impressed by Henri de Busscher’s playing (CD II tracks 13-15). The different performances of the J.C. Bach Sinfonia, Brahms’ Violin Concerto and the Beethoven Variations provide invaluable comparisons of different schools of oboe playing.

In order to come as close as possible to the original performance, every effort has been made to arrive at the correct playback speed and corresponding pitch. This also explains why not all tracks are at the same pitch. 440 Hz was common in England and the US early in the century (with some exceptions like the Philadelphia Orchestra which established 438 as its standard under Stokowski, and the Boston Symphony Orchestra which played at 444 at Koussevitzky’s insistence). Meanwhile on the Continent 435Hz was the norm and the higher Old Philharmonic Pitch (452Hz) was still current in military bands. For more on this topic see my interview by James Brown The Oboist as Custodian of Orchestral Pitch, accessible from the Contents above. Copyright Geoffrey Burgess 2005

Geoffrey Burgess, compiler, was born in Sydney, Australia. While still studying at Sydney University, he performed regularly with the leading Australian orchestras and ensembles, including the Australian Chamber Orchestra and The Australian Opera. In 1983, a Netherlands Government Scholarship enabled him to study Baroque oboe with Ku Ebbinge at the Royal Conservatorium, Den Haag. Shortly after he was invited to appear with numerous European early music ensembles, notably the Paris-based opera company Les Arts Florissants with whom he has performed now for over twenty years. Geoffrey has also toured extensively as a soloist and chamber musician and has given recitals around the world, including at the Utrecht and Boston Early Music Festivals. He is a founding member of The Brandenburg Orchestra of Australia, The Publick Musick (Rochester, NY), and has played with numerous ensembles around the North East, including the Washington Bach Consort, Tafelmusik (Toronto), Concert Royal and ARTEK (NY), and the Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra. He has recorded music of the Bach family for oboe and harpsichord, and appears with Elaine Funaro as Duo d’amore, a group promoting newly-commissioned music for Baroque oboe and harpsichord. Geoffrey is also an active scholar. His 1998 doctoral dissertation on seventeenth and eighteenth-century French opera written for Cornell University was awarded the Donald J. Grout Memorial Prize. He has also published extensively on subjects relating to the oboe including articles for the New Grove Dictionary, and a history of the oboe written in collaboration with Bruce Haynes (Yale University Press, 2004). He has taught at SUNY Stony Brook, and Duke University and is currently living in Central Massachusetts where he is a Fellow of the Five Colleges.

Lani Spahr, audio transfer engineer, has done digital transfers and editing for Sony/France, Boston Records and the National Flute Association (US). He is also a leading performer on period oboes, is a member of Boston Baroque, The Handel & Haydn Society Orchestra of Boston and performs frequently with Tafelmusik in Toronto. In addition, he has appeared with many of the country’s leading period instrument orchestras, including Philharmonia Baroque, The American Classical Orchestra, Boston Early Music Festival Orchestra, San Luis Obispo Mozart Festival, Concert Royal, Philadelphia Classical Orchestra, The Lyra Concert, Connecticut Early Music Festival Orchestra and Arcadia Players. Also a modern oboist, Mr Spahr is formerly the principal oboist of the Colorado Springs Symphony Orchestra, the Colorado Opera Festival, the American Chamber Winds, the Maine Chamber Ensemble. He made his European solo debut in November of 1999 playing the John McCabe Oboe Concerto with the Hitchin Symphony Orchestra in England and in the summer of 2000 presented a solo recital at Imperial College, London. He has served on the faculties of Colorado College, Phillips Exeter Academy (NH) and the University of New Hampshire Chamber Music Institute. Mr Spahr has toured throughout North America, Europe and the Far East on period and modern oboes and has recorded for Telarc, Naxos, Vox, Music Masters and L’Oiseau Lyre.

"Generally speaking, the larger the sampling, the more meaningful the effort. One is thus very glad to have no less than 140 minutes of recorded oboe playing from eight different countries over a full half-century recorded here." Michael Finkelman, The Double Reed (USA)

"My first salvo is a word of praise to the 'backroom boys' [Lani Spahr, for the transfers] - like translators they should be honoured. My second is to Geoffrey Burgess whose notes are fulsome and full of the kind of specialist detail that enhances a historical project such as this. Biographical detail fuses with technical, tonal and expressive analysis in a compact and articulate way." Jonathan Woolf, Classical Music Web

"What a fantastic recording! The quality is amazing, and the playing, and the variety. I'm bowled over!" KB, London

"I wanted to write and thank you for these great discs. What a good project, very educational for us all. I was especially impressed with Bleuzet." Bruce Haynes

"I just want to say how impressed I am by the CDs. It is just fascinating and I have read all the notes - Geoffrey Burgess has written so well and am delighted by some of the rare info he has unearthed - more about Addimando and Labate for instance, than I have ever known. The three versions of the J.C Bach Sinfonia are especially interesting and it really is all totally absorbing to me!" Laila Storch

"The set is wonderful! I want to get more!" Terry B. Ewell PhD; Chair, Department of Music, Towson University, and Former President of the International Double Reed Society

No recordings, but the next best thing - a book by the late James (Jimmy) Brown with biographies of more than 1650 players from the 19th Century, including their solo repertoire. For example, this is Joseph D Ellen, principal oboe in the New York Philharmonic from 1867 to 1900, occasionally playing English Horn (from 1900 to 1904 he was English Horn only). It's called 'Our Oboist Ancestors' |

| back to top | to main catalogue |